Survey: America’s top economists expect double-digit unemployment rate into 2021

The Bankrate promise

At Bankrate we strive to help you make smarter financial decisions. While we adhere to strict , this post may contain references to products from our partners. Here's an explanation for .

The U.S. economy cracked under the coronavirus’ pressure — and piecing the financial system back together will take much longer than it did to fall apart, according to the nation’s top economists.

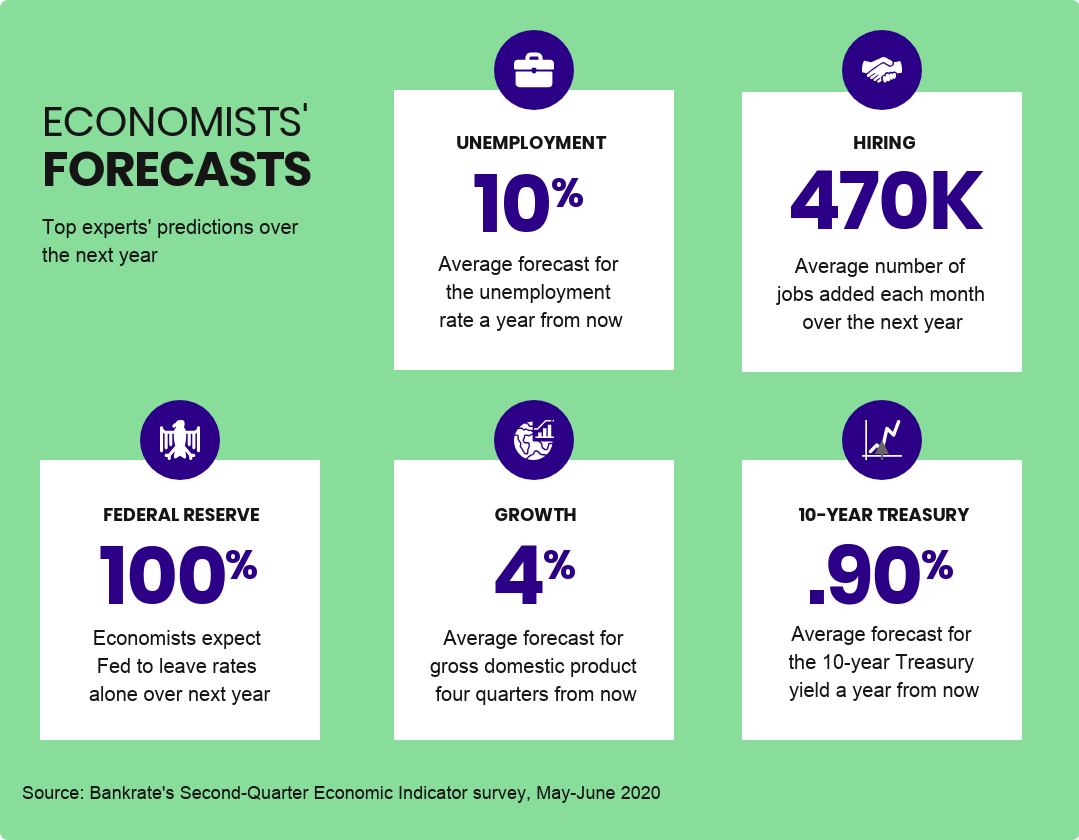

A year from now, joblessness is expected to be in the double digits, the U.S. economy is expected to be much smaller than it was at the beginning of 2020 and the Federal Reserve is unanimously seen as keeping interest rates unchanged at near-zero, Bankrate’s Second-Quarter Economic Indicator poll found. It’s a protracted period of economic malaise so severe that 1 in 8 economists say the U.S. economy has entered its first true depression since the 1930s, meaning the pandemic caused a far worse downturn than the Great Recession of 2007-2009.

“We remain in uncharted waters with respect to the economic outlook,” says Mark Hamrick, Bankrate’s senior economic analyst. “The hope, indeed, the expectation is that a recovery will begin to gain traction as the nation re-opens for business. How much traction exactly remains to be seen.”

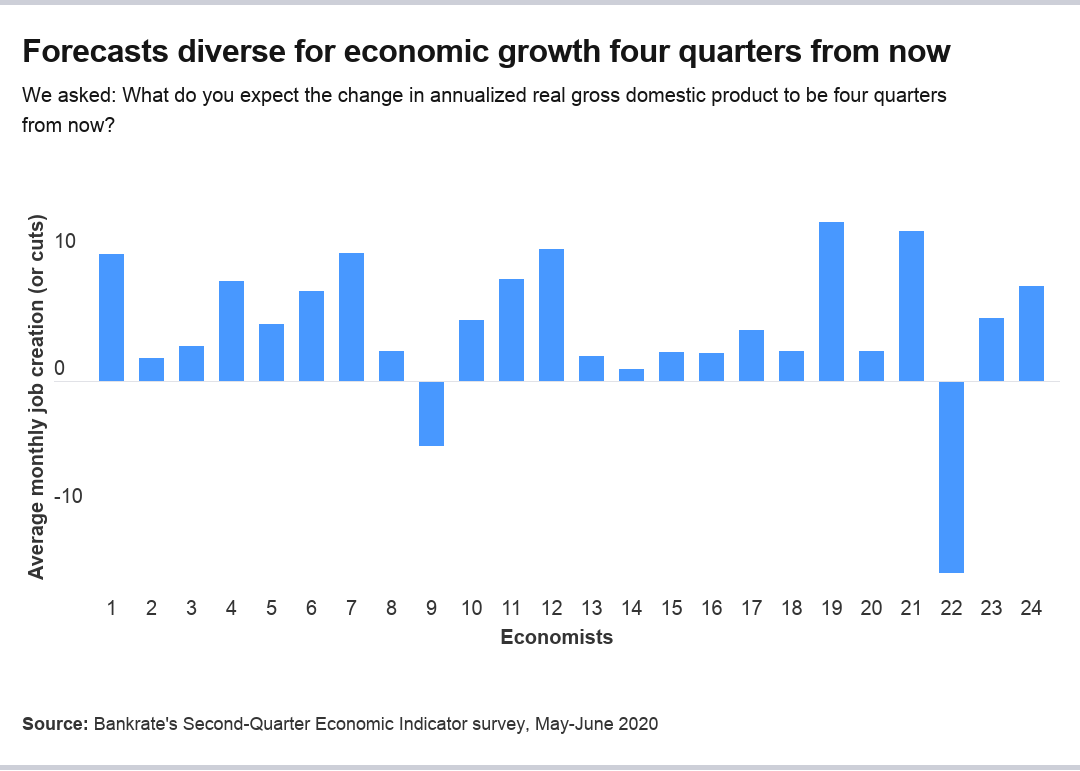

Forecasts show a historically wide range of views when it comes to predicting how much damage the crisis has caused. Yet the thesis is clear: The U.S. economy is unlikely to get back on track anytime soon.

Read on for key findings from Bankrate’s economists’ survey, which polled 24 experts on where they see growth, the job market, the Federal Reserve and benchmark interest rates heading over the next 12 months.

Key takeaways:

- Economists see 10 percent unemployment a year from now.

- Experts divided on how many jobs the economy will add each month over the next year.

- Are risks over the next 12-18 months well-balanced or tilted toward the downside or upside? Experts are split.

- U.S. economy seen as growing by 4 percent four quarters from now.

- Interest rates will continue to hold at historically low levels.

Economists see unemployment at 10 percent a year from now

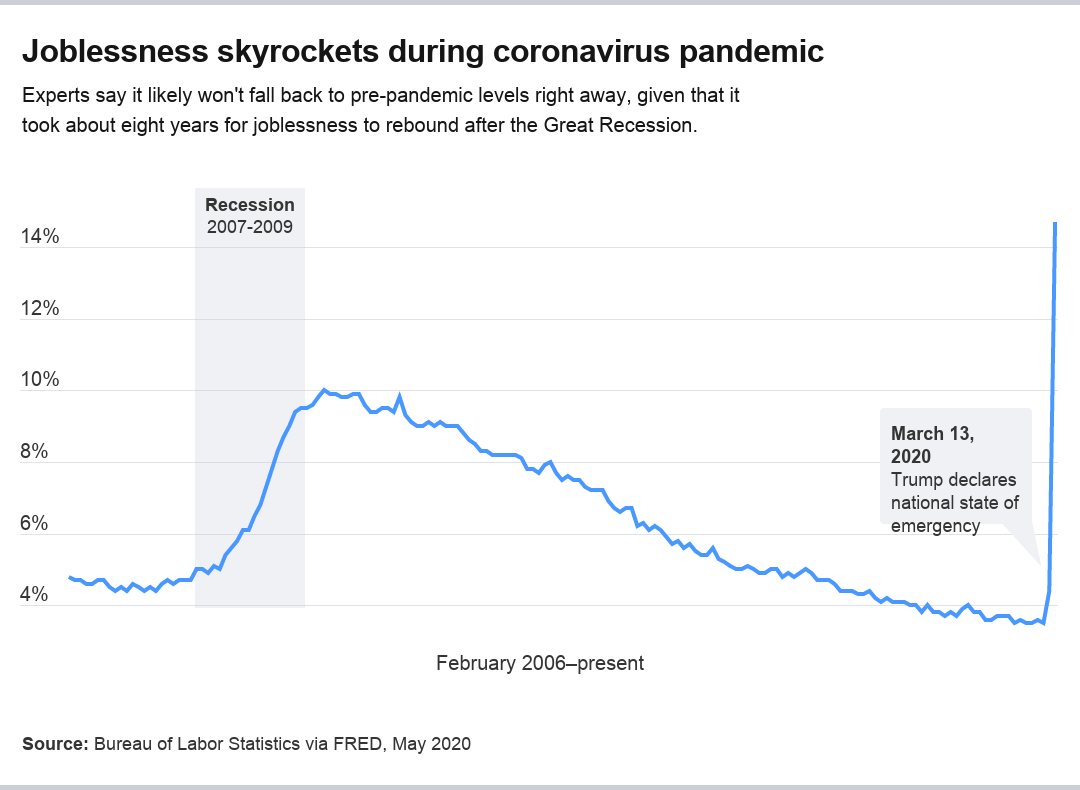

The U.S. labor market is shattering records — but they’re not the ones you want to break.

Employers cut 21.4 million jobs between March and April, two months when almost all states had imposed some kind of shelter-in-place order. Deigned to keep as many people home as possible, the restrictions closed everything from factories and construction sites, to offices, restaurants, theaters, gyms and retailers big and small.

It seems like a seismic cratering compared to total job losses during the Great Recession: 7.4 million. And it means the labor market erased in just 60 days virtually all of the gains that were a decade in the making. After the Great Recession ended in June 2009, firms added 21.5 million jobs over the decade-plus long expansion.

Economists’ unemployment rate forecasts averaged out to 10 percent, according to the survey. Yet responses were wide-ranging, with the highest forecast being 20.1 percent and the lowest being 6 percent. Divergence aside, it all suggests joblessness will likely edge down from its current level of 14.7 percent, but it won’t fall anywhere near the half-century low seen before the pandemic: 3.5 percent.

“The U.S. labor market was crushed by COVID-19, and the recovery will take years,” says Ryan Sweet, senior director of economic research at Moody’s Analytics. “Even if job growth averages our forecast, there will be an enormous hole left to fill.”

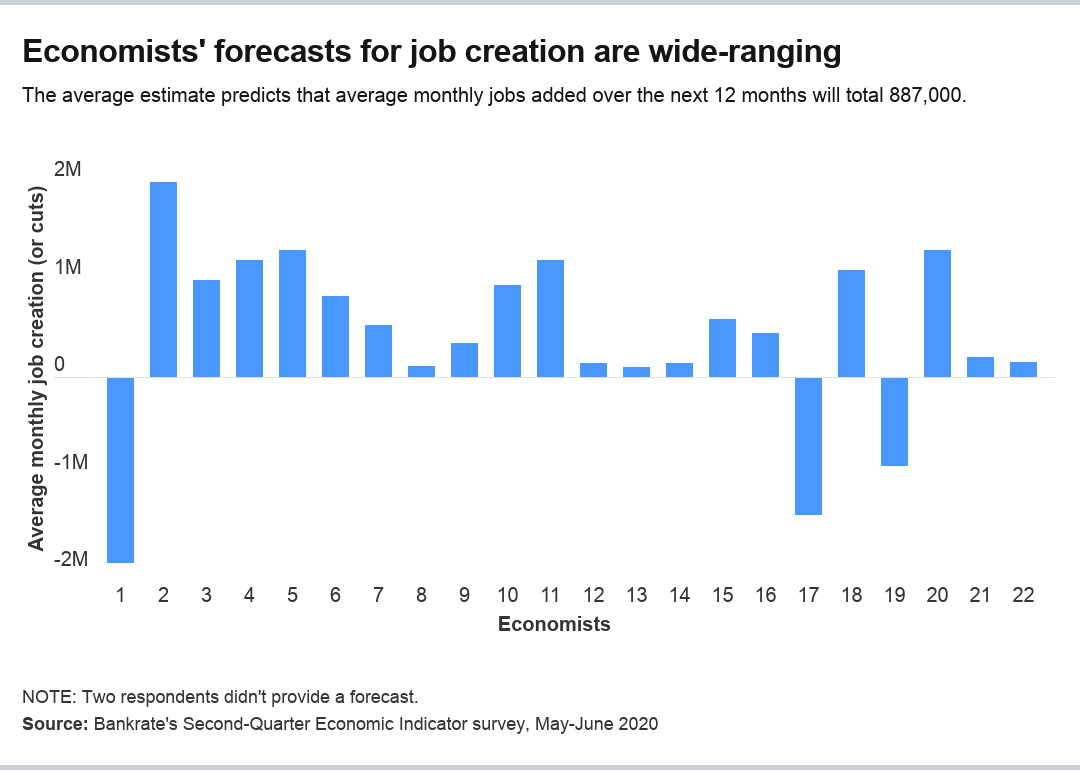

What will hiring look like over the next year? That’s unknown

But it’s a different story when it comes to forecasts for average monthly job creation over the next year. One economist expects that employers will cut an average of 1.9 million jobs a month over the next 12 months. Another, however, sees average monthly job gains reaching 2 million. The median forecast predicts that the U.S. economy will add about 450,000 jobs every month over the next year, while the average of all estimates sees a monthly gain of about 470,000.

It’s all because the path forward is wrought with unknowns. While online retailers are likely to fare better, it won’t be enough to offset the gap in tourism, hospitality, dining and entertainment. Meanwhile, fear of contracting the virus could mean that consumers stay home long after the shelters-in-place are lifted, leading to subdued business investment and hiring.

A separate Bankrate poll from May found that nearly 2 in 5 Americans expect to shop less at brick-and-mortar stores after the pandemic.

“Absent assistance to states, at least 20 percent of the 20 million employed are at risk,” says Constance Hunter, chief economist at KPMG. “The multiplier impact of slower activity could mean job losses trickle in for the remainder of the year. We see double digit unemployment numbers as far as the eye can see.”

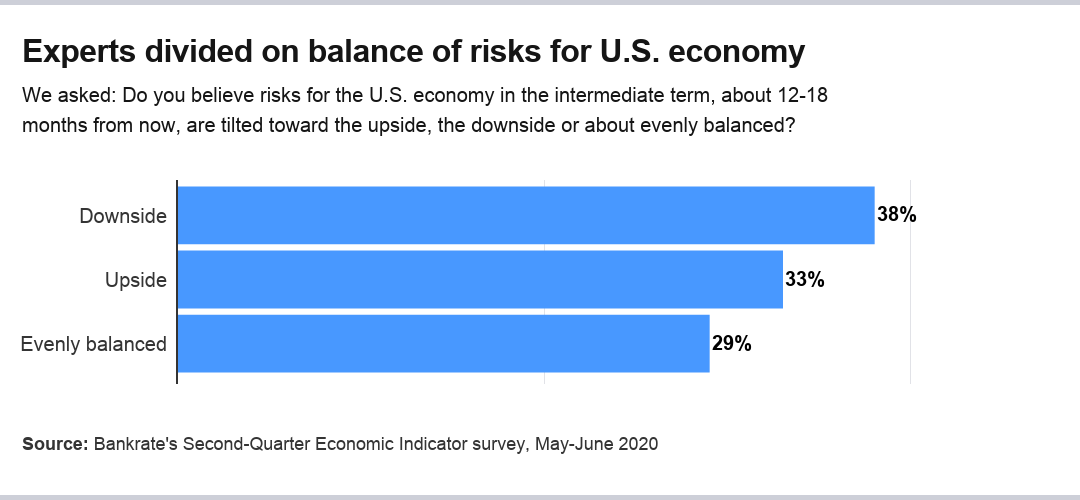

Are there more downside risks than upside? It’s a toss up

Highlighting the divergence of economic forecasts, the nation’s top economists aren’t exactly sure whether the risks are evenly balanced or tilted toward the downside or upside.

Most (38 percent) say risks are tilted toward the downside over the next 12 to 18 months, but not by much. A third of experts said risks are evenly balanced, while 29 percent said risks are to the upside. That’s the widest range of responses in the history of Bankrate’s economists’ poll.

Compare that with the 87.5 percent of economists in Bankrate’s first-quarter poll who said that risks were tilted toward the downside, and it might suggest that economists are at least a bit more upbeat. But the U.S. economy is still facing a serious threat.

While nearly 13 percent say the economy is in a depression, 79 percent say the U.S. is in a recession. Just 8 percent say this downturn is something else.

“The U.S. economy is currently in a sharp and deep recession, but it remains to be seen whether it turns into a true depression,” says Scott Anderson, chief economist at Bank of the West. “Much will depend on how the virus spreads and evolves, the final tally of government support, and if a workable vaccine is found in time.”

U.S. economy seen as growing by 4 percent four quarters from now

When times are good, the U.S. economy grows. But when times are tough, the broader system contracts. That’s been the underlying story during the coronavirus pandemic, as hiring comes to a grinding halt and consumers tap the brakes on spending.

During the first three months of 2020, the U.S. economy shrank by 5 percent, according to the Department of Commerce’s second estimate on gross domestic product (GDP), which is the broadest scorecard of the U.S. economy. It’s notable because states’ shelter-in-place orders were only in effect toward the end of March, days before the quarter ended.

It means that the second quarter of 2020 will show that the U.S. economy shrank unlike levels no one’s ever seen before. A forecast from the regional Federal Reserve Bank in Atlanta’s GDPNow tracker shows the economy collapsing by 52.8 percent, the worst quarter in U.S. history.

“The U.S. economy is a casualty of the coronavirus pandemic and will suffer a sharp contraction in the second quarter of 2020 because it’s hard to spend when you have to stay at home,” says Odeta Kushi, deputy chief economist at First American Financial Corporation. “The historic job losses in the second quarter will be a significant drag on consumer spending. While this economic downturn is likely to make history in its severity, it is expected to be short in duration.”

Even if activity picks back up, experts aren’t expecting that the economy will make up what it lost to the pandemic. Four quarters from now, annualized real GDP will show that the U.S. economy grew by 4 percent, according to both the average and the median forecasts in Bankrate’s poll. The high end of those estimates shows the system expanding by 12.5 percent, while the low end shows the economy contracting by 15 percent.

It’s partially because consumer spending will remain subdued, with households hit hard by unemployment, economic uncertainty and a fear of still getting sick. That might spill over into business investment and hiring.

“Abstracting from vaccine issues, even a year from now, households will still be trying to rebuild their balance sheets, while businesses will be looking to invest in labor-saving capital, not expansion,” says Joel Naroff, president of Naroff Economics. “Thus, trend growth, at best, is likely to be the case.”

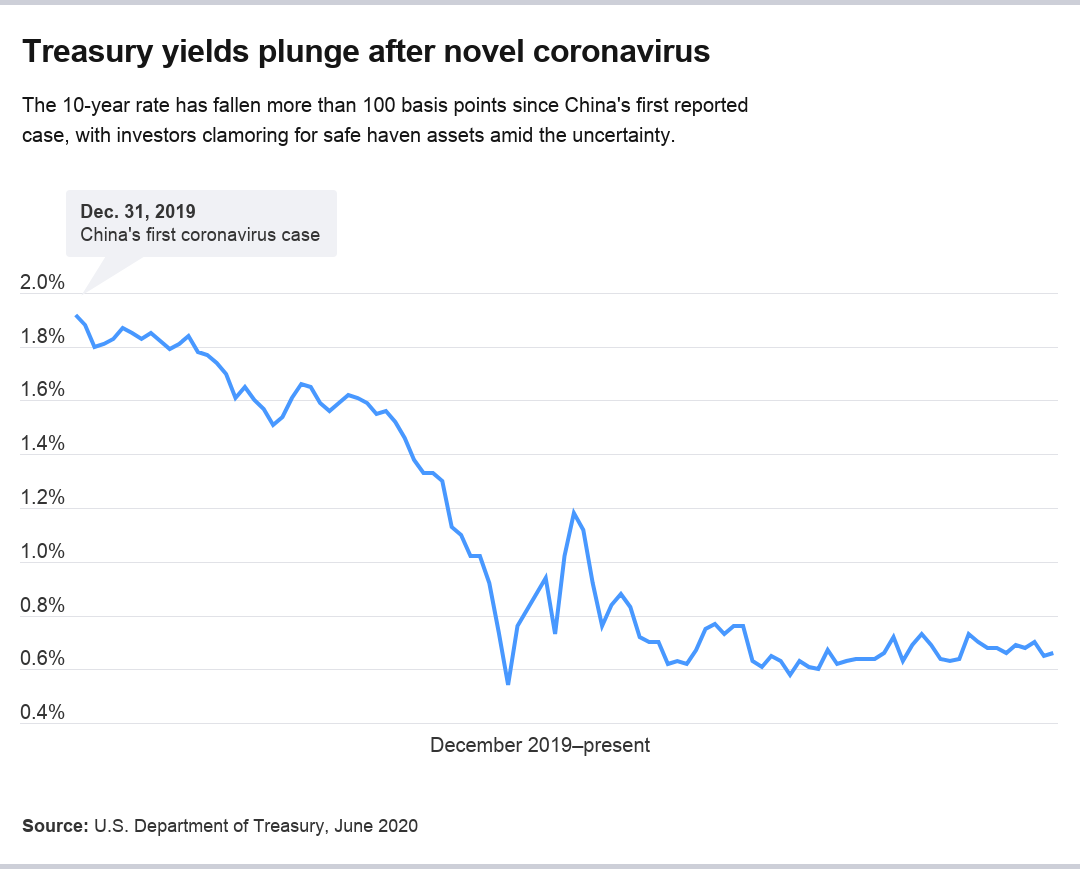

Interest rates across the curve to hold at historically low levels

How much you’ll pay to take out a mortgage, buy a car or swipe your credit card is heavily contingent upon where the broader U.S. economy is heading. Given that most economists expect that growth won’t run off the rails, it foreshadows that borrowing costs will likely hold at their historically low levels.

All of the 24 experts polled for Bankrate’s poll say the Fed will hold interest rates at zero over the next 12 months — where they’ve been holding since March 15, when officials on the U.S. central bank voted to reduce them to a target range of 0-0.25 percent at two emergency meetings within 13 days of each other. The Fed more directly dictates where interest rates on the shorter end of the curve track, such as rates on credit cards and auto loans, bills that don’t require as long of a time horizon to pay off.

But longer periods of borrowing, such as a mortgage, aren’t expected to rise anytime soon either. The average forecast for the 10-year Treasury rate — which serves as a benchmark for the 30-year mortgage — shows yields holding just under 1 percent, at 0.90 percent, a year from now. That compares with 0.66 percent, where the benchmark yield held when Bankrate’s survey period closed.

What this means for you

There’s one piece of tried-and-true financial advice that rings even truer during the coronavirus pandemic: Building up an emergency fund is crucial.

No one knows how long the recession will last or how bad it will get. Trim your expenses and find ways to cut back, so you can sock more money away in the event of unexpected job loss. If you’re carrying credit card debt, consider whether a balance-transfer card is right for you, so you can lower your monthly payment and interest costs down the line.

“Despite the damage done to many Americans’ personal finances, best practices still hold true, including the need to save and pay down, or pay off, debt as possible,” Hamrick says. “Although joblessness is elevated, the majority of Americans still employed should stick to their financial game plan which involves saving for emergencies and for retirement.”

Meanwhile, if you’re thinking about buying a home or want to lock in a lower rate, now is the time. Shop around for the best rate, and you might find one that’s below 3 percent — the mecca of all mortgage rates.

But perhaps adding to the uncertainty, it can’t be forgotten that 2020 is full of many more twists and turns, with it being an election year.

“With the grim outlook for the job market and the broader economy, President Trump’s prospects for re-election have been dealt a sharp setback,” Hamrick says. “He could previously point to historically low unemployment and a booming stock market. Instead, the economy’s unprecedented difficulties have become the focus.”

Methodology

The Second-Quarter 2020 Bankrate Economic Indicator Survey of economists was conducted May 12-21. Survey requests were emailed to economists nationwide, and responses were submitted voluntarily online. Responding were: Scott Anderson, executive vice president and chief economist, Bank of the West; Scott J. Brown, chief economist, Raymond James Financial; Ryan Sweet, director of real-time economics, Moody’s Analytics; Bernard Markstein, president and chief economist, Markstein Advisors; John E. Silvia, president, Dynamic Economic Strategy; Mike Fratantoni, chief economist, Mortgage Bankers Association; Yelena Maleyev, associate economist, Grant Thornton LLP; Lindsey Piegza, Ph.D., chief economist, Stifel; Lynn Reaser, chief economist, Point Loma Nazarene University; Joel L. Naroff, president, Naroff Economic Advisors; Robert A. Brusca, chief economist, FAO Economics; Steven William Rick, chief economist, CUNA Mutual Group; Jim O’ Sullivan, chief U.S. macro strategist, TD Securities; Tenpao Lee, Ph.D., professor of economics, Niagara University; Robert Hughes Senior, research fellow, American Institute for Economic Research (AIER); Danielle Hale, chief economist, realtor.com; Issi Romem, Ph.D., economist and founder, MetroSight; Lawrence Yun, chief economist, National Association of REALTORS(R); Robert Dietz, senior vice president and chief economist, National Association of Home Builders; Odeta Kushi, deputy chief economist, First American Financial Corporation; Robert Frick, corporate economist, Navy Federal Credit Union; Mike Englund, chief economist, Action Economics; Bill Dunkelberg, chief economist, NFIB; and Constance Hunter, chief economist, KPMG.

(Featured image: Photo by Adobe Stock; Illustration by Bankrate)

Related Articles

Survey: Top economists say U.S. economy won’t be fully recovered from pandemic 12 months from now

Survey: Top economists see elevated COVID-19 joblessness for at least another year

Survey: Top economists see slowing economic recovery from coronavirus pandemic in 2021

Survey: Top economists see unemployment rate holding above pre-pandemic levels into 2021